Gaza Is Not a Slide Deck

Showpiece Dispatch 20

Detail from image in the slide deck, shown here desaturated. The original images can be viewed via the link below.

October 23, 2025

At the end of summer, the Washington Post reported on and released a 38-page “deck” that outlined a redevelopment plan for Gaza. Titled “The GREAT Trust,” the document allegedly circulated among Israeli and US officials.

Reading through the presentation, I braced for the inevitable assessment: that this proposed Gaza skyline looked like “a new Dubai.” Dubai often functions as someone’s shorthand for singular capitalist excess, even though the city is enmeshed in a global circulation of ideas and money. The deck’s lead image indeed resembled a standard aerial view looking down Dubai’s major axis Sheikh Zayed Road, named after the former president of the UAE. In the proposal for Gaza, the new corresponding axis is named after Zayed’s son, Mohammed bin Zayed Road. One tower along it looks like the estranged sibling of the existing Emirates Towers duo. And beyond them are luxury islands.

The deck is hardly polished. It was workshopped in group chats. There are typos (“Safe Heaven” for “Safe Haven”), warped charts, pasted-in logos, stock photos modified with AI. Cobbled together from the ideographic script of business-speak, it reads like the deck any middle manager, anywhere in the world, might crank out. Kate Wagner, the architectural critic for The Nation, called it an “awful plan,” which it obviously is. It also, obviously, panders to the US president’s references to a “Riviera of the Middle East.”

Critics have singled out awfulness in the way the plan costs out human displacement: $23,000 saved for every Gazan who agrees to leave, after an offset of a $5,000 payout and “relocation support” for their self-exile. Those who choose to remain would be relegated to prison-like “humanitarian transfer areas.” Land claims would be translated to crypto tokens, a system with a bad track record for people not already rich.

Life lived as an emergency. Fenced in temporary housing for those who decide to remain during reconstruction, called “humanitarian transfer areas.” From “The GREAT Trust Plan.”

It’s tempting to dismiss the document as an amateurish aberration, but it originates from desks at the management consulting firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG). Its logic is familiar. Their competitors McKinsey & Company sketched up Dubai’s Healthcare City, Saudi Arabia’s economic cities, and more recently Neom. Who knows how many similar decks BCG has made. Management consultants have designed cities less as homes for residents than as investment products. It’s bad enough that partners at BCG budgeted an exile; worse is that they believed themselves qualified to do it.*

Any talk of “voluntary” displacement summons a century of Palestinian exile and ongoing land grabs, even before you add the two million who have been displaced these past two years. This deck fuses that history with the unavoidable displacements caused by large-scale redevelopment projects.

Architecture, at any scale, requires moving massive amounts of resources: dug up, sorted, compiled, transported, and assembled. In any large-scale development, human displacement is the less-spoken constant. Workers move to mine the materials, to build the structures, and then to maintain them. They are then priced out of staying. The pages of such proposals rarely acknowledge these required migrations, but in an awful way—through mass exile or “humanitarian transition areas”—this plan expresses no shame in saying the quiet part out loud. In Gaza, the violence remains explicit and lasting.

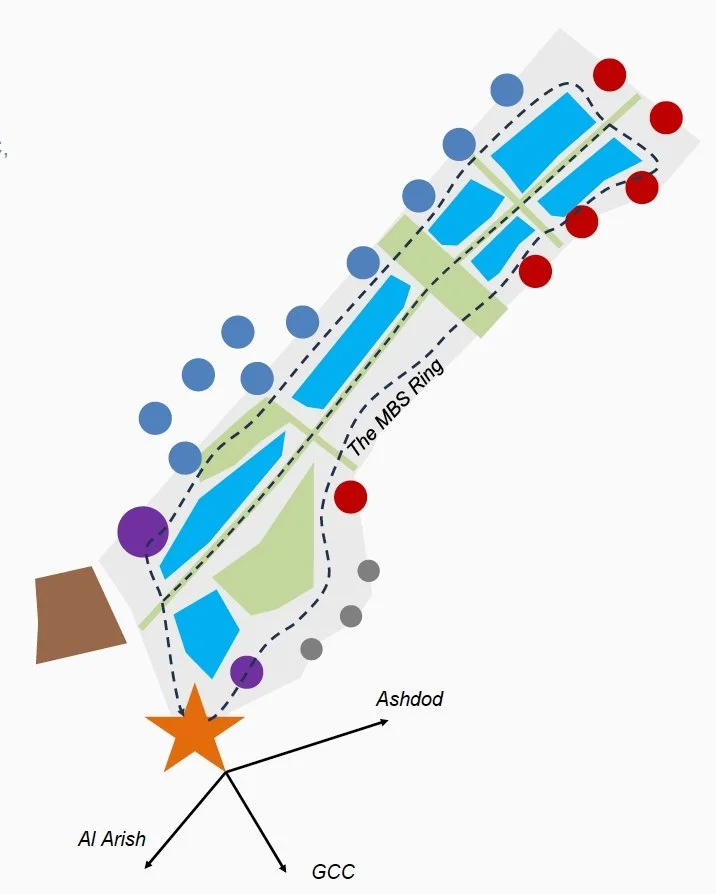

Diagrammatic plan from “The GREAT Trust Plan.” Blue dots signify luxury man-made islands named Trump. Red are “Elon Musk Smart Manufacturing Zones.” Plan was written before Musk’s departure from US White House.

Exciting Development Ideas

I wrote the above before the current ceasefire was enacted, when it still seemed possible the killing might stop. Since its issue, few have acknowledged the deck, but its leaden spirit found its way into the 20-point ceasefire:

#10: A Trump economic development plan to rebuild and energize Gaza will be created by convening a panel of experts who have helped birth some of the thriving modern miracle cities in the Middle East. Many thoughtful investment proposals and exciting development ideas have been crafted by well-meaning international groups, and will be considered to synthesize the security and governance frameworks to attract and facilitate these investments that will create jobs, opportunity, and hope for future Gaza.

#11: A special economic zone will be established with preferred tariff and access rates to be negotiated with participating countries.

“Thriving modern miracle” and “exciting development ideas” are terms one might not associate with a ceasefire, but now it is clear just how tied together destruction and construction can be. In the diagrammatic plan above, we can read the blue dots marking Trump-branded artificial islands as a rehearsal for the “Trump economic development plan.” For years, prospects of development projects in the Gulf have piqued the interest of Trump and his family.** And it is clear they remain a steady reference point for US political efforts in Gaza. As Trump well knows, such “miracle” projects will require money from elsewhere, and there are signs that the shopping for investors has begun.

Just this week, the Financial Times feature on Mohamed Alabbar, the CEO of Dubai’s state-backed developer Emaar, made no reference to Gaza. His “spree of overseas projects” does include a huge $17 billion investment in Egypt. But compare that figure to the Great Trust’s rough estimate for just clearing rubble and ordnance and installing basic infrastructure and emergency housing: $43.6 billion. More recently and directly, Alabbar addressed whether he had interest in rebuilding Gaza: “It's my philosophy ... that everybody should clean up his garbage. I'm very focused on making money for my shareholders.” Alabbar, perhaps the embodiment of the so-called Dubai development model, knows its limits. His assertion—that those who destroyed Gaza should fix it—seems to play out in real time: the US vice president refers to Jared Kushner as “the investor,” and the US president–led “board of peace” suggests an illegal foreign occupation. The Wall Street Journal reports that “If the peace plan proceeds, Kushner and [real estate developer and Trump’s special envoy to the Middle East Steve] Witkoff will be deeply involved in a Gaza reconstruction effort.”

“The GREAT Trust Plan” estimated 5 years of ordnance removal and site clearance at $9 billion. Image from plan. With a fictional name on excavator, it appears AI-generated, perhaps based on post-earthquake efforts in western Syria in 2023.

Plans before Peace, by Design

Plans to rebuild Gaza go back earlier than you might think. Hardly two months after Israel Defense Forces launched its first large-scale attacks, the United Nations appointed Dutch politician Sigrid Kaag as Senior Humanitarian and Reconstruction Coordinator for Gaza in December 2023. Kaag says the assumption around her appointment had been that the attacks would be brief. As that assumption unraveled, she was one of the few outsiders to witness the scale of destruction firsthand. Still, she drew up a plan: “We thought out the best scenarios for the reconstruction and who could lead it.” She claims her team studied what would be required to clear vast areas of unexploded ordnance, clean up wreckage, and rehouse people. She adds that her reconstruction plan addressed the thousands of bodies that will be found in the rubble. “You cannot just come in with earthmovers. People need the chance to say goodbye with respect.” Her departure was announced around the time that The GREAT Trust was leaked. Did it ever reach her desk? What happens to her “best scenarios” now?

I’m reminded of a recent post by the Palestinian journalist Abubaker Abed, written in response to the White House’s 20-point plan:

Just to be clear: No one has the right to comment on the proposal except the people of Gaza—those who lived the genocide. Even Palestinians in the West Bank and the diaspora must stay silent and be all ears. All others must listen, not talk.

That would be a true place to start, but there’s hardly a Gazan at current tables for peace talks. When it comes to the future of Gaza, its people must also be the ones to design it. For now, design remains a violence in its own right. As Kaag mentioned, ample time will be necessary to mourn those found under the rubble. The poet Doha Kahlout writes, “When we say ‘we’ve lost our city’ we mean that a civilization has been destroyed.” The extent of mourning is and will continue to be unfathomable.

What makes this deck awful is that it’s fathomable. We’ve seen it all before. No architect was hired to make it. Text prompts into AI and a menu of options in PowerPoint sufficed. In response to the deck, some have called on architects to turn down future work offers. We’ve heard this before: don’t design for Dubai, for Abu Dhabi, for Doha, for Neom. Maybe some will refuse or walk away, as Sigrid Kaag did. More likely, from regional headquarters in Dubai or Riyadh, the world’s largest firms wait for the phone to ring. After the violence, the reconstruction is just another “real estate bonanza.” The deck shows, in fact, that reconstruction doesn’t follow violence; it’s bound up in it.

As correct as Abed’s insistence is, it will take a lot to protect it. One consistency in Gulf urban development projects is that, even with reserves of cash, they need international investment. Gaza’s destruction has resulted from a clear and limited set of actors; its reconstruction will require complex networks of money and expertise that build the world around us. Making something is always more difficult than destroying it.

Five years after finishing Showpiece City, I still look back on what I learned from Dubai and how deeply we’re caught in a web of our own expectations.

Notes:

* BCG claims that two partners were “exited” for the displacement calculation, though their names remain unpublished. The company said they misrepresented BCG by also working on the plan that resulted in the creation of the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation.

** Trump had high hopes for a hotel and residential tower on Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah in the early 2000s. The 2008 financial crisis flattened the plan into a park with a running track.