Temporary by Degree

Showpiece Dispatch 13

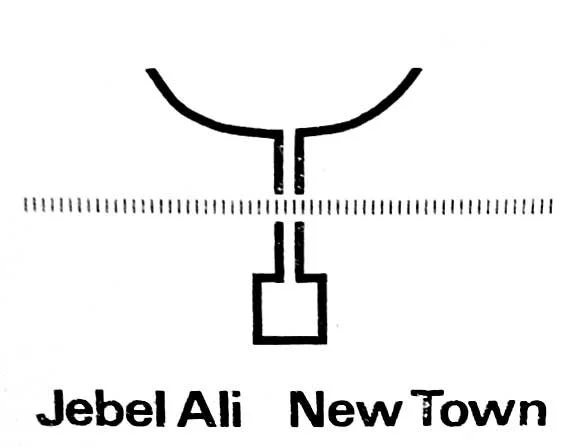

From cover to report by Peddle Thorp Chapman Taylor, 1976.

9 September 2021

Forty-five years ago today, Dubai’s ruler commissioned Peddle Thorp Chapman Taylor to design Jebel Ali New Town. Little evidence of the firm can be found, other than that it no longer exists. It was likely a short-lived, and unsuccessful, fusion of two established architecture firms, both with global ambitions for large-scale contracts.*

By 1976, British “new town planning” had already shaped Dubai. As early as the 1960 town plan, concepts associated with British new towns—such as the neighborhood unit, the roundabout, a hierarchical road system, and the even dispersal of amenities—had been used to grow Dubai, but no attempt had yet been made to create a separate new town. Hardly six months after being commissioned, Peddle Thorp Chapman Taylor presented a design for Dubai’s first new town, just without any of the those recognizable new-town ingredients.

Weeks before the planners acquired their new commission, the engineering firm Halcrow had announced plans for Port Jebel Ali. It was the firm’s largest project to date in Dubai. As detailed in Showpiece City, a modest research assignment had first brought Halcrow to Dubai in 1954. Just over twenty years later, Jebel Ali promised a port project worth at least $1.6 billion ($6 billion today). Patience had paid off.

When Peddle Thorp Chapman Taylor submitted its plan for Jebel Ali New Town as the living component to Halcrow’s giant industrial complex, plans for this part of Dubai near the Abu Dhabi border were cloaked in mystery. A model was reportedly kept locked up at the engineer’s Dubai offices. Around the time of the UAE’s federation in 1971, there had been talk of a new city, to be named Karama and located somewhere between Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Many wondered whether Dubai’s leadership was going ahead to build the new capital within Dubai’s borders. Journalists reported that the new town would focus on industrial aspects and leave business and trading to the existing city. Rumors of big ambitions proved true, as the planners estimated in their unpublished plan that the population of Jebel Ali New Town could reach 750,000.

In Dubai Amplified, Stephen Ramos provides a clear overview of the plan. (The book’s cover includes an enticing rendering commissioned by the planners.) Rather than repeat Ramos’s work, I focus here on an aspect of the planners’ approach to housing. Like the 1960 town plan, Jebel Ali’s housing needs are divided into three categories: the “most important” being unattached villas for the wealthiest residents; the middle-tier composed of various denser, more urban options; and then there was the third which accommodated the least paid workers, including the construction workers who were scheduled to leave upon completion of their work.

It is noteworthy that the plan devoted so much attention to the third category. Beyond just that attention, the plan addresses an aspect of life often overlooked by urban planning, namely the sense of temporary that pervades life in Dubai.

There is also an acknowledgement that temporariness is hierarchical, with the lowest-income residents more exposed to its risks. The planners calculated that after the initial construction phases, the number of lower-income residents would not decrease but actually rise because construction workers would be replaced by larger numbers of industrial workers presumably residing there for a longer period. Beyond just estimating the change in the make-up of Jebel Ali’s lower-income population, there also seems to be the assumption that they would be perhaps financially, and personally, better off.

This is made clear in the plan’s presentation of how “Housing Type 3” would work. In overview, the housing takes form over a distributed grid of courtyard buildings that surround a souk, a mosque, and perhaps some community amenities. In addition to the designated amenities, one can begin to read different kinds of public space that could arise in the spaces between buildings. Another set of drawing reveals how the courtyard buildings could function at first in two ways: either as corridors of bunkbed dormitories or as chambers of individual “bedsitting rooms.” For both options, there would be shared kitchen, bathing, and toilet facilities. A third configuration of the courtyard building demonstrates how, once less temporary workers moved in, corners of the square could be apportioned into three-bedroom courtyard houses. This final iteration suggests that a later generation of lower-income workers could be joined by their families.

This housing scheme catches my attention for two reasons. First, it is an unusual recognition that urban planning needed to consider the temporary life in Dubai. There is an acknowledgment that while people might move and whole districts might need to transform, buildings could adapt and endure to those changes. And that leads to the second peculiarity of this scheme, namely that it endorses a durable but flexible kind of building. By proposing a building type that could endure multiple cycles of urban growth and multiple types of users, the plan sets up the expectation that buildings should be built to last. In 1976, it was still common that a new building went up with the expectation it need not survive longer than whatever time it took to make a good profit off of it. Dubai was hardly ever a renter’s market, so an owner’s profit scheme often included eventual demolition to start again with something larger, higher, and newer.

In the late 1970s, it was still common that Dubai’s construction workers lived in canvas tents or plywood shacks, which were raked up at the end of a construction project. The so-called labor camps today, while more permanent, often come down after only several years—a sign of their quality of construction and the attention to their maintenance. These proposed courtyard buildings at Jebel Ali New Town remind me of caravanserais or hospitals of the Mediterranean Renaissance that housed itinerant populations with resounding flexibility and still continue to exist centuries later by housing people and new uses.

In regard to the massive, high-risk dimension of the Port Jebel Ali industrial complex, Halcrow held firmly onto the project, withstanding any criticism that such ambition could bankrupt the city. As Ramos recounts, Jebel Ali New Town got shelved.** In place of the new town, Halcrow delivered Jebel Ali Village, a lattice of villas around a community center—less a new town, more a company compound. The versatile courtyard building also got shelved, and I cannot think of a project in Dubai that ever captured its spirit of reuse.

Revisiting “Housing Type 3” reminded me of recent news stories about the UAE’s efforts to rewrite local visa polices to afford non-nationals more permanence. There is, for example, the “100,000 Golden Visas for Coders.” Simeon Kerr writing for the Financial Times reported of reforms for “liberalising residency rules to attract and retain skilled workers” whose residency is currently connected to a single employer. For me, the Jebel Ali courtyard building launches a whole line of questions about whether, beyond any new visa policy, Dubai’s built environment can accommodate a flexible but dedicated population. Can its offerings of speculative development offer the golden coders and any other valued freelancers a place suitable for them? Will coders really want to play the real estate speculation game in order to make a home? Will gig-economy workers who survive on flexible rental contracts ever find a culture of annual lease contracts suitable to their unsteady lifestyle?

Part of the lure to invest in real estate has to do with an aura of permanence. And today, that promise of permanence still evades the swath of land once designated for Jebel Ali New Town. In the early 2000s, the site was rebranded with a terraformed palm and a new name, Waterfront City. It boasted the capacity to double the emirate’s population. For now, there exists on that land two labor camps which are kept separated from any city life by a guard station and a hardly passable road. These fenced-in accommodations are an indication that the frustration of being temporary might be the only thing that remains permanent.

* The Chapman Taylor part of the firm had recently completed a project in Newcastle called Eldon Square, a “retail center” that introduced the American shopping mall craze to Great Britain.

** Al Maktoum International Airport, a sliver of whose plans opened in 2010, fulfills the ambitions for the second airport. In the early 2000s, Nakheel’s Dubai Waterfront, including a “downtown” designed by OMA, was reminiscent of the earlier plan.